In Ramallah, Running

Guy Mannes-Abbott and Samar Martha, editors

Black Dog Publishing, 2012

In his 1997 memoir I Saw Ramallah, Mourid Barghouti identified the early stage of what is now called the Ramallah “bubble” or “syndrome.” Writing on the state of Palestine just a few years after the Oslo Accords, Barghouti locates a “mirage” or “idea of Palestine” that distracts native inhabitants.

Ramallah, it is argued, has been redeveloped with a focus on gross commercialization through an unsavory brand of urban planning. While the outer limits of the “bubble” enclosure of the city are defined by the spread of nearby settlements and a section of Israel’s snaking wall, this open-air prison is made increasingly grotesque with an internal barricade that mirrors the swell of the occupation—only vertically into the airspace in the form of high-rise buildings. Public areas, once serving a variety of critical functions, have been annexed as part of the new plan, producing an inextricable psychosocial space: a realm of blanket escapism. Many residents are left with a bitter sense of frustration that is directed inward; understandably so, for comparison, there are enough superbly polished mega bubbles in the region that attempt to disguise deplorable political networks.

Reflecting on his return to the West Bank after a thirty-year absence, Barghouti asks, “What deprives the spirit of its colors? What is it other than the bullets of the invaders that have hit the body?” In Ramallah, Running poses similar questions at a time when many of the city’s artists and cultural practitioners are searching for ways to intervene in its present-day crisis. Edited by Guy Mannes-Abbott, a London-based essayist and critic, and Samar Martha, an independent curator and co-founder and director of the non-profit organization ArtSchool Palestine, this 2012 book brings together twelve writers and artists, some Palestinian, others who have spent time in the Occupied Territories. The project is introduced by Jean Fisher and includes an excerpt from a forthcoming novel by Adania Shibli and prose by poet Najwan Darwish. A range of recent visual art by Sharif Waked, Jananne Al-Ani, Mark Titchner, Olaf Nicolai, and Paul Noble is featured alongside these texts while artists Khalil Rabah, Emily Jacir, and Francis Alÿs offer earlier works that keep with the publication’s overall theme.

Although In Ramallah, Running was realized as a collaborative experiment, it originally began as a series of short form texts that Mannes-Abbott penned following a brief stay in the city. While participating in a residency at the A.M Qattan Foundation, the author set out to find the extreme points of Ramallah’s borders (geographic and otherwise), running and walking through its neighborhoods and to its outskirts, many times in riskier areas near settlements and IDF outposts. A self-described “bubble-burster,” this ritual became an exercise in observation. “When I am not running, I’m thinking, details stack up. The present acquires depth and dimension, things become complex,” he writes. Could these limits be breached, exposing the built-in susceptibility of power or place? How much ground could he cover each day? To what extent would his foreign appearance protect him from sniper viewfinders, allowing him to travel farther than most residents? By regularly leaving this “bubble” then returning with little disturbance or hassle (although never guaranteed), what could be deduced about the area that might be unattainable in its inner, current position? Invoking Mahmoud Darwish’s poem “We have on this earth what makes life worth living,” he writes:

I wanted to discover the limits to what this means. Not the limits of freedom, because there is none here, but of “this earth,” of what there is “to live for,” of that “something” itself. That “something to live for” is the freedom to work against these very limits, to have a meaningful life.

[Mark Titchner, "On This Earth There is Something to Live For" (2011). Copyright the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and Vilma Gold, London.]

[Mark Titchner, "On This Earth There is Something to Live For" (2011). Copyright the artist. Image courtesy of the artist and Vilma Gold, London.]

Mannes-Abbott narrates with a certain tempo as he processes the daily details of this Palestinian setting. His descriptions of the landscape, the hilly, rock-strewn surface that seems to beckon under the weight of his steps, are tenderly complex, frequently in appreciation of the understated generosity of its rough, embracing terrain. At the same time there are raw, to-the-point moments within these texts, passages that jolt the reader back into a “hellish vision”:

I know the well-documented history of shootings and massacres, the bottomless impunity of soldiers and settlers… I feel exceedingly exposed to their mercy; a very strange sensation… I step to the highest point of the track, hoping they might have the decency to shoot me in the legs. Realise they don’t but that—like so many children, passers-by, protesters before me—I will not hear the explosion in my head.

This back and forth between the brink of violence and relative calm appears to consume the air, a tension that is captured in his fourteen entries; and to which many of the book’s contributors respond. Some do so directly, keeping in pace with the author by burrowing into this non-space and extracting details of its strata. Others circle its parameters, uncovering the grip of the occupation’s tentacles. It is to the credit of his navigable writing (what Mourid Barghouti has called its “cunning simplicity”) that each included work determines its own status within the project, not one overshadows another, and each adds something more. Had he not reached out to his peers, Mannes-Abbott’s poetically attentive series could have stood on its own. By doing so, however, the author initiated an interventionist art strategy that should be studied by future practitioners.

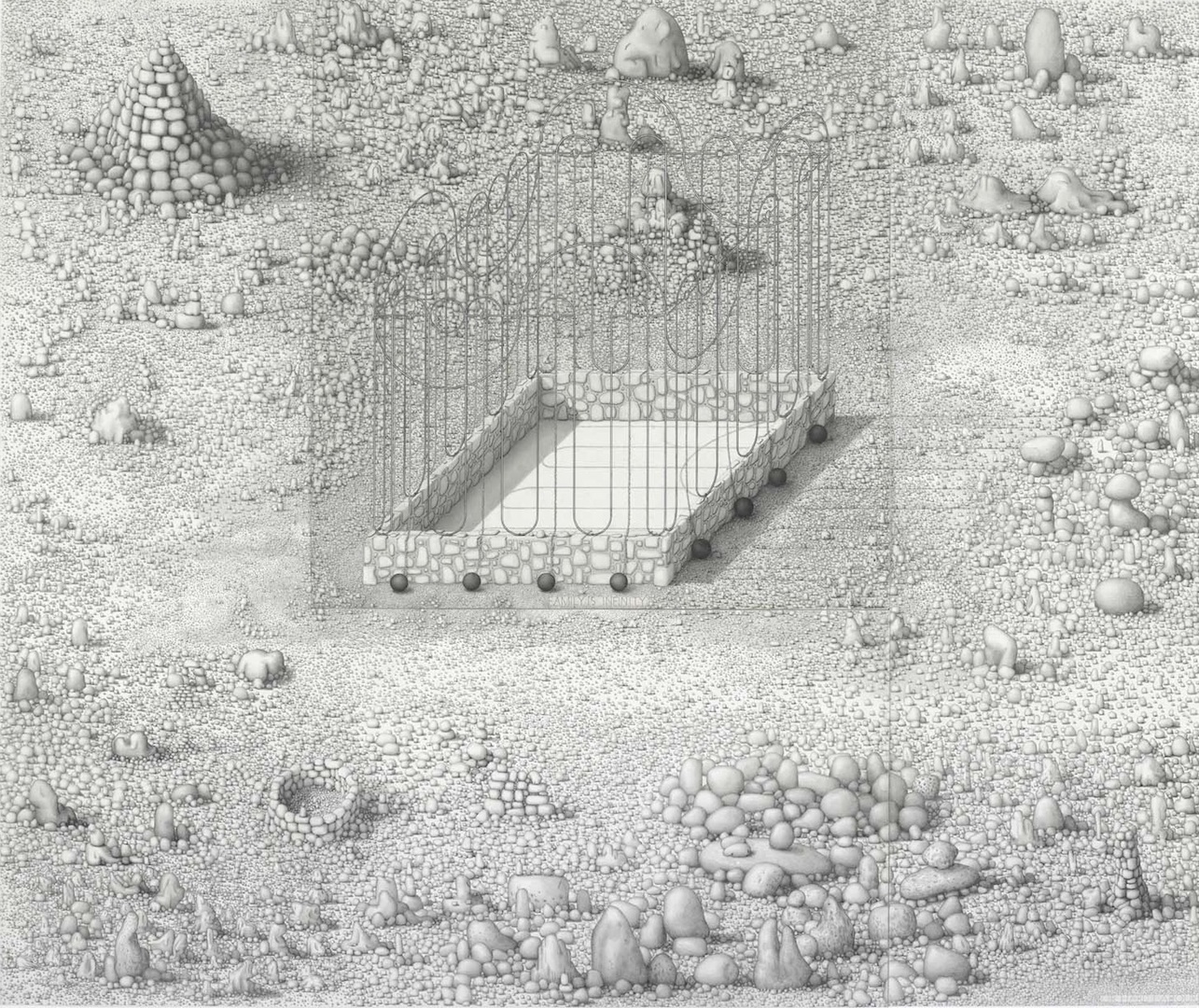

[Paul Noble, "Family is Infinity (or Hard Labour)" (2011). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.]

[Paul Noble, "Family is Infinity (or Hard Labour)" (2011). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery.]

Adania Shibli’s excerpt intentionally meanders as she writes from the perspective of a Ramallah resident whose contempt for the occupation has boiled over into a paralyzing focus on the mundane. Worsening this mindset are the city’s related borders, above all its social demarcations, which are implemented to create “an empty life that enjoys everyone’s respect.” Her central character’s tedious obsession with the trivial aspects of life is familiar to those who have been forced to endure the misery of war—when days lose their color, accumulating as dust mounds that slowly bury one alive. It is actually a defense mechanism, a move towards isolation that somehow provides shelter. Olaf Nicolai fittingly adds a new cover of his “Sigmund Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia,” an Arabic translation of the psychoanalyst’s text that was released as a self-made pamphlet and radio broadcast in the West Bank in 2009. As Nicolai explains in an accompanying artist statement, Freud addresses “the two basic psychological mechanisms to handle the loss of objects.”

Selections from Sharif Waked’s “Beace Brocess 2” (2011), a series of ink and highlighter works on paper, show two figures (presumably Yasser Arafat and Ehud Barak) as they engage in a series of interactions. Waked’s protaganists are drawn as angular, abstracted outlines, their forms hollowed, existing without detail or substance. As though the artist has a 360-degree view of this robotic dance, Arafat’s trademark keffiyeh is shown in various poses. The politically loaded headdress is filled in with a vibrant lime green, a color that is also present in the depictions of Barak but only in minor areas of his features such as his hands or hair. Through a number of seemingly forced gestures that read like a stop motion animation, Arafat appears to exert the most effort in executing this ritualistic display. In a scene just before the monumental clinch (plate #14), Barak’s highlighted arm resembles the sillouehtte of a gun that is pointed directly at his Palestinian counterpart.

[Francis Alÿs "Gold-leaf Wall" (2005). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of the artist.]

[Francis Alÿs "Gold-leaf Wall" (2005). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of the artist.]

A 2004 UN-issued map of road closures in the West Bank prefaces Francis Alÿs’ “Gold Leaf Project” (2005). Its legend shows sections of the wall (planned and built) as it cuts through the Palestinian territory and enfolds a section of Israel. A total of fifty-two closures are listed for the month of March that year, including checkpoints, roadblocks, observation towers, and “earth mounds.” In a serene, barren landscape of coarsely painted hills, Alÿs has decorated the western side of the wall, which acts as a fortress for Israeli settlements, in shimmering gold leaf, an ornamental effect that is traditionally reserved for religious imagery or the frames of official portraiture, in other words: emblems of power. This delicately aestheticized view of such an abhorrent sight is also reminiscent of the murals of landscapes that were painted by settlers when portions of the wall were first erected: self-imprisonment masquerading as paradise.

“Right and Right” (2000), a centerfold by Khalil Rabah of two loafers (the kind belonging to business men) similarly lends to evocative ambiguity. One is more polished than the other, as both are the right-side shoes of different pairs. Essentially useless, they provide little in the way of functionality despite signs of being worn. Rabah`s still-life images are part of a larger body of work that has been exploring an "idea of Palestine" for some time. While mockups representing an official notion of statehood or objects that would point to signs of a national infrastructure and culture at first feel humorous and playful, there is also an element of tragedy to them in the fact that every detail of Palestine, even the meaningless symbols of state showmanship, are forever stifled. And yet the artist`s objects and performances can also be read as supreme displays of an existentialist at work. In Palestine, history has shown, everything and nothing are certain; definitions and boundaries appear where others have been erased. There is no better way to test or defy the arbitrary nature of limits than to create that which embodies everything yet is bound by nothing.